MEDICAL MALPRACTICE CAUSING BRAIN DAMAGE OR DEATH

Introduction

There is now compelling evidence that medical errors are the nation’s third leading cause of death, trailing only heart disease and cancer.

Examples of fatal errors I have seen in my own practice are listed below in Section I.

When a patient suffers a bad outcome, it is reasonable to seek an explanation and, in particular, to ask if a medical error played a role in the outcome.

As discussed in Sections III-VII, harm resulting from medical errors remains very common. When there is evidence that a medical error led to an injury, it’s important to determine if patient safety recommendations for preventing that type of error were followed.

I. Medical errors and hospital misconduct causing brain damage or death in cases I have litigated

Anesthesiology (see Anesthesia Malpractice)

Chiropractic Manipulation

Inappropriate (contraindicated) neck manipulation of 60 year-old man, resulting in stroke and permanent disability

Emergency Room Medicine

Negligent discharge of patient with ruptured duodenum due to trauma from truck accident, resulting in death

Failure to recognize fetal distress, resulting in newborn brain damage (cerebral palsy)

Hospital Administration (associated with a case of medical malpractice)

Negligent administration of emergency room, resulting in newborn brain damage (cerebral palsy)

Negligent administration of obstetric service, resulting in newborn brain damage (cerebral palsy)

Cover-up of cause of patient’s death

Hospital Liability for Negligence of a Nurse (Vicarious Liability)

Negligence of ER nurse—death

Negligence of labor and delivery nurse—birth injury (newborn brain damage)

Negligence of nurse anesthetist—maternal brain damage

Neurology

Inappropriate prolonged high dose steroid therapy and failure to monitor steroid immunosuppressive effects, resulting in life-threatening pneumocystis carinii pneumonia requiring lengthy treatment in ICU and causing permanent disability (plaintiff was a physician)

Nursing Home Negligence

Failure to recognize respiratory distress from developing pneumonia, resulting in death

Obstetrics (see Obstetric Malpractice/Birth Injuries)

Pediatrics

Failure to recognize developing sepsis in 3 year-old from duodenal rupture caused by minor abdominal trauma, resulting in brain damage

Delay in diagnosis of meningitis in 2 year-old, resulting in brain damage

Radiology

Delay in diagnosis of breast cancer resulting from failure to recognize breast mass on mammogram of 50 year-old woman, resulting in death

Error in prep for an intravenous pyelogram (IVP) causing kidney failure and cognitive impairment in 40 year-old man

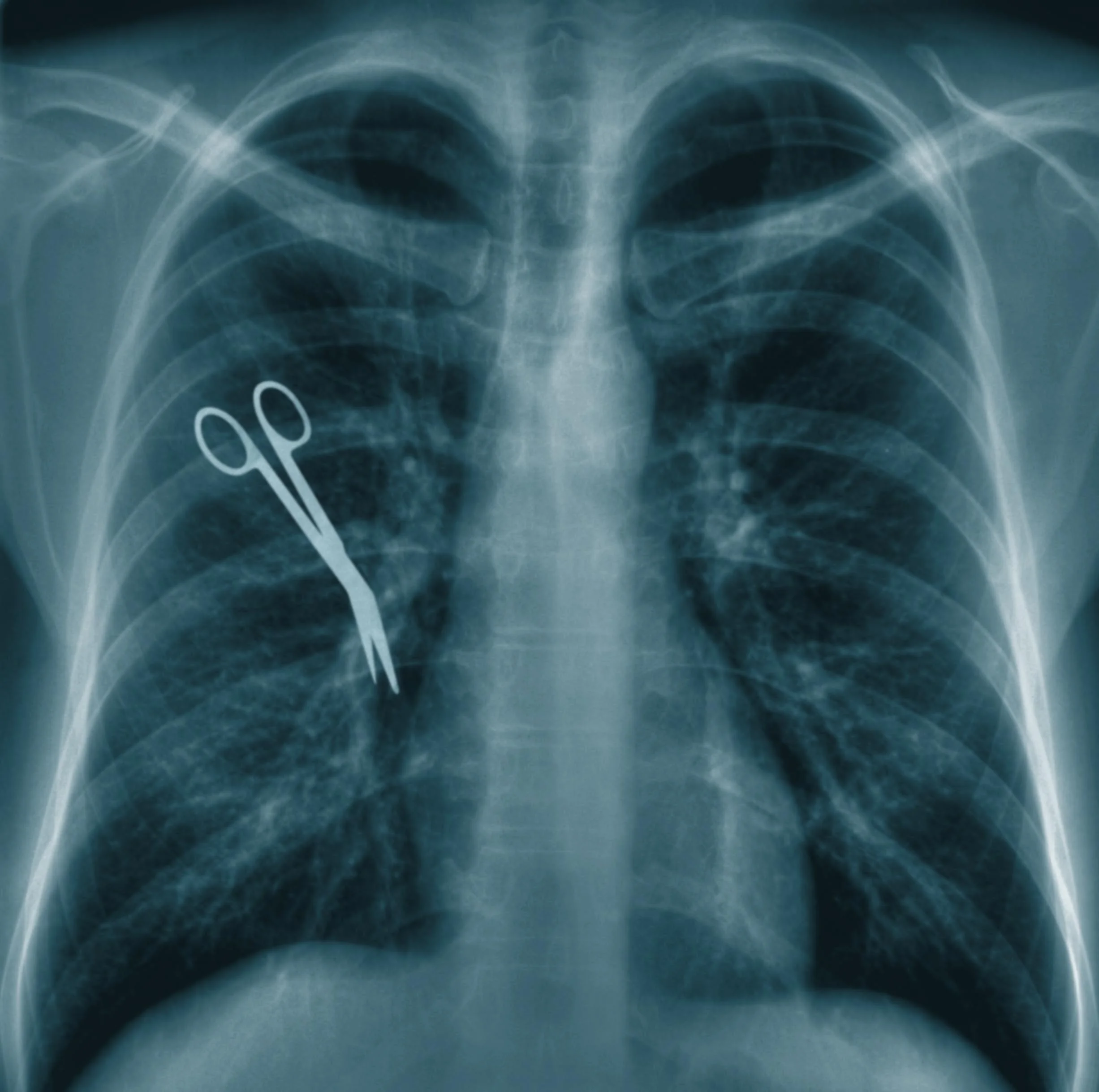

Surgery

Injury to bile duct during gall bladder operation, resulting in sepsis and other complications from permanently damaged bile duct

Injury to ureter during hysterectomy followed by failure to recognize developing sepsis, resulting in brain damage

Negligent administration of unnecessary transfusion which transmitted the AIDS virus and caused the death of a 50 year-old man from HIV/AIDS.

All of those cases resulted in a confidential settlement or trial verdict for the Plaintiff.

II. Experts

All of those cases were hotly disputed and all of them involved a battle of expert witnesses. That’s what happens in most cases, regardless of how well-founded a case may be. And that is why it is so important to recruit highly respected expert witnesses and be prepared to attack your opponent’s experts with scientific evidence from medical journals and texts.

See Experts for some of the expert witnesses I recruited for my cases.

III. The Risk of Medical Errors and the Rise of the Patient Safety Movement

For every disastrous case like the ones listed above, there may be many hundreds of cases in which good doctors delivered good care. How great, then, is the risk of falling victim to a medical error?

“Hospitals are dangerous places… I feel almost the same about surgicenters, free-standing emergency rooms, and urgent care facilities.”

Those are not the words of a wary patient. They are from an article entitled, “Will Medicine Ever Become Safer?,” written in 2013 by a former editor of the Journal of the American Medical Society, George Lundberg, M.D. (1)

Dr. Lundberg’s article addressed the subject of medical errors. He lamented the limited success of what is known as the patient safety movement. That movement’s research on the problem of medical errors and its recommendations for preventing them can play an important role in the analysis and litigation of a medical malpractice case.

The patient safety movement arose in the mid-1990s after a succession of highly publicized cases of medical malpractice.

The first occurred in December, 1994 at a prominent Boston hospital. Betsy Lehman, a reporter for the Boston Globe, died there after being given a four-fold overdose of a chemotherapy drug on four consecutive days.

Two months later, in February, 1995, Willie King had the wrong leg amputated by a surgeon at a Tampa hospital. A month later, a patient at the same hospital died after a respiratory technician mistakenly disconnected his respirator.

A few months later, in May 1995, a neurosurgeon at a New York hospital operated on the wrong side of Rajeswari Ayyappan’s brain after bringing another patient’s X-rays into the operating room.

Then, in December, 1995, 8-year-old Ben Kolb went to a hospital in Stuart, Florida to have minor ear surgery. He was mistakenly given an injection of adrenaline, a powerful stimulant, instead of a local anesthetic. Ben went into cardiac arrest and within hours, the little boy was dead.

The public furor over these cases spurred the American Medical Association (AMA) and some other organizations to create the National Patient Safety Foundation in 1997. The mission of the Foundation was to develop techniques to prevent medical errors.

That was quite a turnaround for the AMA. As Lucian Leape, M.D., a Harvard professor and pioneer in patient safety, has said, “In the past, the AMA sort of pretended the problem didn't exist or that it was extremely rare. There was a lot of denial.” (2)

IV. The 1999 Institute of Medicine Report

1999 was a watershed year for the patient safety movement. That was the year that the Institute of Medicine (IOM), a branch of the National Academies, issued a famous report entitled, “To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System.”

The IOM Report charged that, “These horrific cases that make the headlines are just the tip of the iceberg.” It declared that mistakes and unsafe practices in U.S. hospitals killed up to 98,000 patients a year, a number which it likened to the death toll if if a jumbo jetliner crashed every single day for a year. (3)

The key messages of the IOM report were:

there are serious problems with the quality of health care delivery;

these problems stem primarily from poor health care delivery systems, not incompetent individuals; and

solving these problems will require fundamental changes in the way care is delivered.

V. “The Penetration of Evidence-Based Safety Practices Has Been Quite Modest”

Ten years later, in 2009, Lucian Leape, M.D. and Donald Berwick, M.D., another expert in patient safety, wrote,

“While efforts to improve patient safety have proliferated in the past decade, progress has been frustratingly slow…

“Healthcare is unsafe. In its groundbreaking report, To Err Is Human, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) estimated that, in the USA, as many as a million people were injured and 98 000 died annually as a result of medical errors. Subsequent studies in multiple countries suggest these may be underestimates.

“The IOM called in 2000 for a major national effort to reduce medical errors by 50% within 5 years, but progress since has fallen far short. Many patients continue to fear, justifiably, that they may be harmed when they enter a hospital.” (4)

Another disheartening message emerged from a 2010 study looking at hospitals in North Carolina. North Carolina was chosen for the study “because of its high level of engagement in efforts to improve patient safety.”

That study “found that harm resulting from medical care was common, with little evidence that the rate of harm had decreased substantially over a 6-year period ending in December 2007…

“Our findings validate concern raised by patient-safety experts in the United States and Europe that harm resulting from medical care remains very common. Though disappointing, the absence of apparent improvement is not entirely surprising.

“Despite substantial resource allocation and efforts to draw attention to the patient-safety epidemic on the part of government agencies, health care regulators, and private organizations, the penetration of evidence-based safety practices has been quite modest.” (5)

VI. Medical Errors Are the Third Leading Cause of Death in the U.S.

Other studies have also observed that the death toll from medical errors is much greater than the Institute of Medicine’s estimate of up to 98,000 deaths in its 1999 report:

In a 2009 article which estimated hospital deaths from diagnostic error alone, two experts on patient safety, David Newman-Toker, M.D. and Peter Pronovost, M.D. wrote, “An estimated 40,000 to 80,000 US hospital deaths result from misdiagnosis annually. Roughly 5% of autopsies reveal lethal diagnostic errors for which a correct diagnosis coupled with treatment could have averted death.” (6)

In 2010, the Inspector General of the US Department of Health and Human Services reported finding that preventable adverse events contributed to the deaths of Medicare beneficiaries at a rate of 79,000 deaths per year.(7)

In 2013, a major study found that over 400,000 Americans die in hospitals every year as a result of medical errors and other preventable harm. This figure makes medical errors the third leading cause of death in America and it does not even include deaths from errors in settings other than hospitals. The study also found that errors causing “serious harm” to hospital patients seem to be 10- to 20-fold more common than errors causing death.(8)

In 2015, the Institute of Medicine issued a report which addressed the “unappreciated” problem of diagnostic errors. It declared, “The delivery of health care has proceeded for decades with a blind spot: Diagnostic errors—inaccurate or delayed diagnoses—persist throughout all settings of care and continue to harm an unacceptable number of patients. For example:

• A conservative estimate found that 5 percent of U.S. adults who seek outpatient care each year experience a diagnostic error.

• Postmortem examination research spanning decades has shown that diagnostic errors contribute to approximately 10 percent of patient deaths.

• Medical record reviews suggest that diagnostic errors account for 6 to 17 percent of hospital adverse events.

• Diagnostic errors are the leading type of paid medical malpractice claims, are almost twice as likely to have resulted in the patient’s death compared to other claims, and represent the highest proportion of total payments.”

The IOM’s 2015 report “concluded that most people will experience at least one diagnostic error in their lifetime, sometimes with devastating consequences. Despite the pervasiveness of diagnostic errors and the risk for serious patient harm, diagnostic errors have been largely unappreciated within the quality and patient safety movements in health care.” (9)

VII. Application of Patient Safety Principles to the Analysis of a Malpractice Case

The upshot of all the research into medical errors and the admonitions of patient safety experts over the past 20 years is that there should be a two-step analysis of cases of possible malpractice:

( 1 ) Did the patient suffer a bad outcome which was caused at least in part by conduct which violated the standard of care for diagnosis or treatment; and, if so,

( 2 ) Was there also a system failure to follow patient safety guidelines or recommendations for preventing the type of error(s) that occurred.

References

1. Lundberg G. Will Medicine Ever Become Safer? At Large at Medscape, November 26. 2013.

2. Boodman S. Diagnosing Medical Errors: In the Wake of Widely Publicized Mistakes, Doctors Try to Make Hospitals Safer. Washington Post, November 19, 1996.

3. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. To err is human: building a safer health system. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 1999.

4. Leape L, Berwick D et al.Transforming healthcare: a safety imperative. Qual Saf Health Care 2009;18:424-428.

5. Landrigan CP et al. Temporal Trends in Rates of Patient Harm Resulting from Medical Care. New Engl J Med 2010; 363:2124-2134.

6. Newman-Toker DE and Pronovost PJ. Diagnostic Errors—The Next Frontier for Patient Safety. JAMA 2009; 301:1060-1062.

7. Inspector General of the US Department of Health and Human Services. Adverse Events in Hospitals: National Incidence Among Medicare Beneficiaries. November 2010.

8. James JT. A New, Evidence-Based Estimate of Patient Harms Associated with Hospital Care. J Patient Saf 2013; 9:122-128.

9. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Improving diagnosis in health care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2015.